Dreaming of a Tactical Messenger Bag

I wish someone would make a tactical messenger bag.

Plenty of companies make what they claim to be a tactical messenger bag: 5.11, Spec-Ops, ITS, TAD, and Maxpedition to name a few. None of these fit the bill. Those bags are all what I would refer to as a side bag or a man-purse. I don’t use that term in a derogatory sense – they’re fine bags, but they’re not messenger bags.

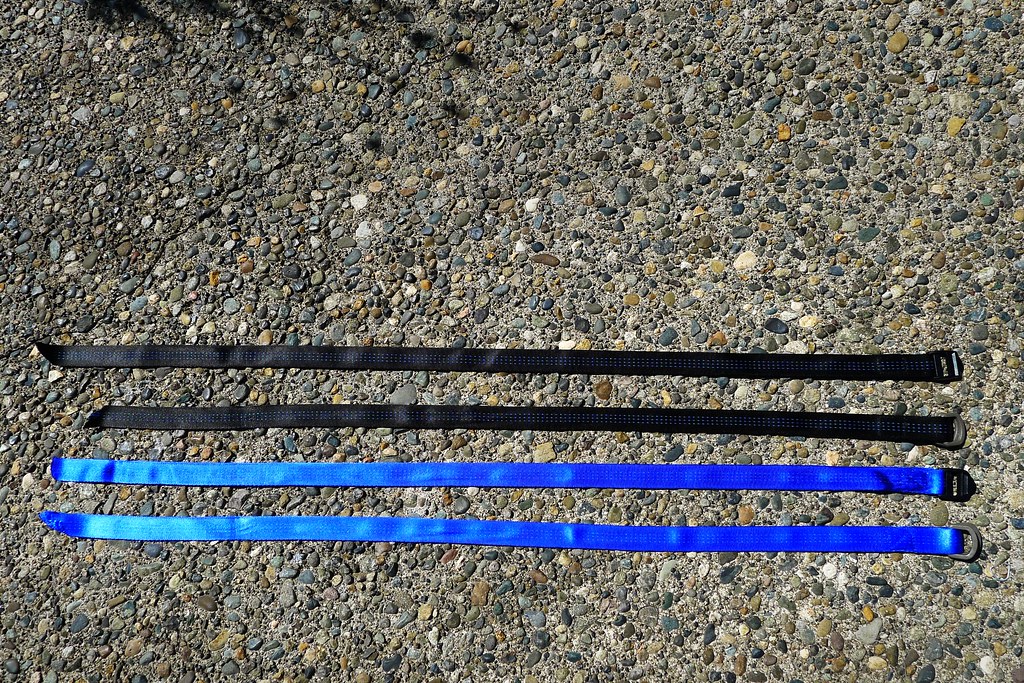

For me, the defining characteristic of a messenger bag is that it designed to be worn on the back, not hanging down on one’s side. Timbuk2, Chrome, Seagull, and R.E.Load are examples of companies that make messenger bags. I want one of those bags, but with the excellent, so-called “tactical” features that the aforementioned companies bring to the market: appropriate use of PALS webbing1, ability to support concealed carry, a quick-access medical compartment2. (Oh, and velcro for my tacticool patches, of course.)

Try riding a bike with a tactical man-purse, and then try riding a bike with a messenger bag. It’s easy to see why anyone with “messenger” in their job title carries an actual messenger bag. The practicality of such a bag isn’t limited to just the bicycle market: try running, or performing any physical activity (particularly a violent one, as might be required by someone with “tactical” in their job title) with a bag flapping on your side. It doesn’t work. Some companies have tried to address this by adding a stabilizing strap to help lock the bag in place. That’s a fine addition, but it is no replacement for a bag that is properly designed in the first place.

I can’t recognize any advantages that the man-purse offers over the messenger bag. The messenger bag, on the other hand, offers distinct advantages over the man-purse.

Notes

- ↵ Don't try to reinvent the admin compartment. Everyone and their mother makes an admin panel. Just give me some PALS and allow me to mount to the admin panel of my choice to the bag.

- ↵ We'll agree that an armed citizen is more likely to need a blow-out kit than someone unarmed. Now just think how much more likely an armed biker is to need something of that sort!