Trail Designs Ti-Tri Titanium Stove System

I’ve had a few requests to do a review of the new stove system I’ve been using for the past couple weeks. I don’t feel like I have enough experience with it yet to do a proper review, but I snapped some photos today to let people know what it’s all about.

The system is a Trail Designs Caldera Ti-Tri Titanium Stove System. It takes the older (and very popular) Caldera Cone and combines some of the know-how of the folks at Titanium Goat to create a light-weight system that burns alcohol, Esbit tabs, and wood. And, of course, it’s made of titanium.

If you already have a pot you’d like to use, you can contact Trail Designs and have them build a cone for you. Elsewise, the Ti-Tri is available with a pot from Titanium Goat. I’ve previously mentioned my love affair with my Snow Peak Trek 700 mug/cup/pot/thing, but I had been thinking of acquiring a larger, 900ml pot for somewhat more extravagant cooking. Because of this, I decided to get the 900ml Ti-Tri from Titanium Goat, rather than have a Ti-Tri built for my Snow Peak mug.

Titanium Goat’s 900ml pot is a basic affair: handles on the body, a decent lid with a thingy on top that allows it to be easily lifted, as well as three holes for venting or draining water. Titanium Goat claims that the pot and mug weigh in at 4.4oz, which seems correct to me.

The Ti-Tri system itself comes inside of the same caddy system as does the normal Caldera. It’s basically two pieces of plastic that screw together. The diameter of the caddy is the same as a 32oz Nalgene, so it will nest in the same cups (such as the aforementioned Snow Peak 700). This is a somewhat bulky way of carrying the system, I find, but the caddy is constructed out of food grade plastic, so both pieces can double as a bowl or mug. It also does a great job of protecting all the components. So far, I’ve been packing everything in the caddy. I haven’t decided if I’ll keep doing it that way or not.

The alcohol stove that comes with the Ti-Tri is a Trail Designs 12-10 which, they claim, has been designed to “perform optimally with the restricted air flow and higher heat retained by the cone during operation.” My expertise in the design of alcohol stoves are lacking and, as I said before, I don’t feel I yet have enough experience with this system to draw a comparison between it and my Vargo Triad XE (which I also haven’t had for all that long), but the 12-10 has seemed extremely efficient so far (and much easier to light).

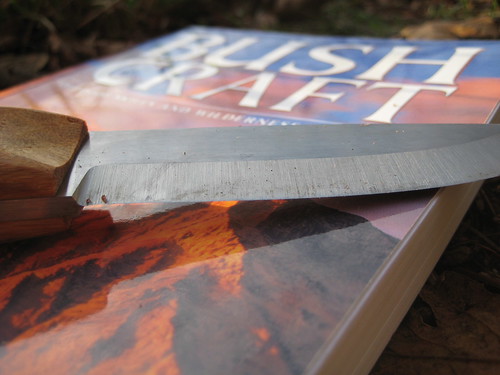

The Ti-Tri cone itself is made from a piece of very thin titanium foil. On either side of the cone is a rib – the smaller slides into the larger, and there’s your cone. It’s very easy to assemble. The cone has air vents on the top and the bottom. When assembled, the cone goes over the stove, and the pot nests into the top.

The pot’s lip holds it up. Even with the thinness of the cone’s material, it is a surprisingly sturdy setup. You do have to be somewhat watchful when sliding the pot into the cone, as the pot handle’s mountings will sometimes get caught on the edge of the cone’s opening. I say sometimes, but this actually happens to me the majority of the time. It’s greatly annoying.

If you’re sure to center the handles over the opening in the side of the cone, the handle mountings will not get caught.

The base is an optional addition to the Ti-Tri system to be used for wood burning. It’s simply another piece of titanium foil, slightly larger in diameter than the cone. When burning wood, you set the cone on the base, put the included titanium stakes through the holes in one end of the cone and out the other. These then support the pot higher up, allowing you to shove your fuel in the cone’s side opening.

The Ti-Tri’s third fuel option are esbit tabs, which uses Trail Design’s GramCracker. The GramCracker

This setup directs the heat for a much more efficient burn than that offered by a standard esbit stove. (The GramCracker also comes with a small piece of foil to be used as a base, but since I already carry the larger base for wood burning, I leave this smaller piece at home.) With the GramCracker assembled, the cone is placed on top, and the pot is nested just as with the alcohol stove.

The Ti-Tri also comes with an 8 oz fuel bottle and measuring cup. The measuring cup holds 1 oz and has measurements marked in various units on all sides. The fuel bottle itself is the best I’ve found for alcohol. It has a tight screw lid that prevents any leaking (unlike those little Nalgene dispenser bottles), but also provides a plug with a small hole that allows one to fill the measuring cup (or the stove directly) much easier than it is to pour without such a plug.

Today, I was planning on using the Ti-Tri as an alcohol stove. Trail Designs claims that the Ti-Tri can bring 2 cups of water to a boil with 15ml of alcohol. I’ve found that 15ml brings 2 cups to more of a simmer. For a boil, you’d want 25ml. I didn’t measure exactly how much water I poured into the pot, so I decided to use a bit over 20ml of fuel.

Tea, today, would be Doug Fir and Cedar. After pouring the the fuel from the measuring cup into the stove, I lit the 12-10 with a match, tossed on the cone, settled in the pot (after getting the handle mountings caught on the edge of the cone), and shifted my attentions elsewhere. I didn’t time it this time around, but I think it burned for a bit over 10 minutes. My water was brought to a full, rolling boil – much more than I really needed just for tea, but I was just out for a day-hike, so I wasn’t terribly concerned with fuel conservation. After the burn, I tossed the Doug Fir and Cedar into the pot to steep and settled in for some tea and poetry.

Overall, the Ti-Tri comes in at just under 10oz. It’s not the lightest or most compact alcohol stove setup, but seems to me to be extremely efficient. It’s a bit like the JetBoil of the alcohol stove world. Of course, the Ti-Tri’s primary advantage over other alcohol stoves is that it is not an alcohol stove: it’s an alcohol stove, esbit stove, and wood stove. Having three different fuel options in your pack (and at such a light weight) is quite an invaluable thing. I’m greatly looking forward to further use and testing of what has become my primary cooking system.

The Ti-Tri is a somewhat new product, but has already garnered some positive press, such as a 2008 Backpacking Light Staff Pick. I’m quite curious as to how the system’s wood burning compares to that of the Bush Buddy.

Check out Trail Design’s gallery for photos further photos of the Ti-Tri in use, including at -20 degrees Fahrenheit in the Yukon.

Today’s post brought to you by: that feeling you get when you dangle your legs over a precipice that could probably kill you. And blue skies.

Bed in the bush with stars to see, Bread I dip in the river -- There's the life for a man like me, There's the life for ever. from The Vagabond, Robert Louis Stevenson