The Laundry Alternative Wonder Wash is a portable, hand-crank washing machine. It is basically a bucket with a sealed lid, mounted on a base via an axle with a handle that allows the bucket to be spun. The bucket is filled with warm water. When the lid is sealed and the machine is spun, the pressure increases, which causes the soapy water to be pushed through the fibers of the fabric being washed. As such, the Wonder Wash results in cleaner garments, and accomplishes this in a shorter period of time, than a traditional electric washing machine that relies on simply agitating the material. It achieves this in a package that is compact, portable, and off-grid compatible.

I purchased a Wonder Wash nine years ago. It has been my primary washing machine for the past five years. It’s a great solution for things like gym clothes that you want to wash frequently and not leave sitting around, getting funky, until you build up a large enough load to justify the use of a typically sized electric washing machine. The small size of the machine makes it easy to store when not in use, which is important for apartment dwelling, as well as the RV market that The Laundry Alternative seems to target. While I doubt the volume of the machine is practical for the laundry generated by a family of four, I find it works great for me. It encourages me to do laundry more frequently than I otherwise would – I typically do 2-3 loads per week – which in turn allows me to own less clothing (and towels, and bedding, etc). I don’t have to consider the it-will-be-AWOL-in-a-laundry-pile-on-the-floor-for-2-weeks factor when determining how many pairs of underwear I need in my life. The gentleness of the Wonder Wash allows me to keep what clothing (and towels, and bedding, etc) I do choose to own in service for longer than I otherwise would if I were regularly treating them to the abuse of a traditional washer and dryer.

I also find the smaller capacity of the Wonder Wash to be useful when washing waterproof garments with a technical wash like Nikwax Tech Wash. I usually only have one or two waterproof garments to wash at a time. With a traditional electric washing machine, I need to use more water and thus more of the expensive soap than is really warranted. With the Wonder Wash I can easily scale down the water and soap to what is appropriate for the load.

My apartment has an electric washer and dryer in the building, but not in my unit. I use it maybe once every 3 months, when I’ve neglected laundry and have enough dirty things that I would need 3+ loads of the Wonder Wash to clean it. If I had an electric washer and dryer in the unit I think I would still favor the Wonder Wash.

Use

The process of using the Wonder Wash is pretty simple.

- Add warm water, soap and clothing to the machine.

- Seal the bucket and spin, about one rotation per second, for 2-3 minutes.

- Dump the soapy water and fill with cold water to rinse.

- Seal the bucket and spin, about one rotation per second, for about 1 minute.

- Dump the water and remove clothing to dry.

The washing and rinsing part of the process take at most 4 minutes. The most time consuming part is filling the machine with water.

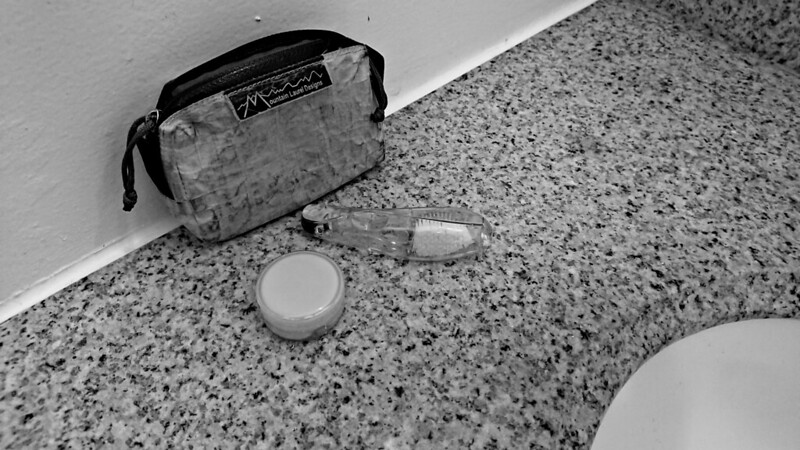

Soap

When I first began using the Wonder Wash I tried it with Seventh Generation Free & Clear Liquid Detergent. This is the soap I have always used in electric washing machines. This detergent is very sudsy, and I found it challenging to use enough soap to clean, but little enough to not require multiple rinse cycles. I quickly gave up on this and moved to Eucalan. I keep this around for occasionally lanolizing wool. Eucalan is a no-rinse soap, which works well in the Wonder Wash. I still performed a single, quick rinse cycle, but if I accidentally used too much soap I didn’t have to worry about ending with excessive suds that would require multiple rinses. Unfortunately Eucalan isn’t the cheapest soap out there.

I used Eucalan in the Wonder Wash for a couple years before realizing that I could probably just use the same soap I used for everything else in my life: Dr. Bronner’s. I shower, shave, wash hands, wash fruit, and clean surfaces with Bronner’s products. It is always effective, tends to be readily available and affordable, and is most likely not giving me cancer. So why not laundry? As it turns out, it works great with the Wonder Wash. I use one tablespoon of the Baby Unscented Castile Liquid Soap for a full load. It’s especially nice for attacking dust mites in bedding.

For the rinse cycle I’ll add about two tablespoons of distilled white vinegar, which helps to remove residue left over from the soap as well as soften the load. This softening is important for heavy cotton things, like towels, which otherwise become quite stiff when air dried.

Drying

Without an additional tool, any time saved by using the Wonder Wash instead of an electric washing machine will be lost after all the wringing required. Laundry removed from the Wonder Wash and placed directly on a drying rack will take days to dry. If electricity is available, the best solution to this is an electric spin dryer. Mine is a discontinued model made by the Laundry Alternative, but they have other models available. These dryers are simply steel drums that spin the clothes really fast to remove the water. It’s similar to the final cycle of an electric washing machine, except they spin much faster (around 1800 RPM). No heat is involved, so they do not shorten the service life of your clothing like a normal heat dryer.

I run the spin dryer until water stops coming out the drain spout, which tends to be around 90-120 seconds. After this cycle, clothing is still damp, but it is impossible to wring any moisture out of it. Something light and quick drying like a Merino wool t-shirt could be worn immediately and dried out with body heat in maybe half an hour, but I move everything from the spin dryer to a drying rack. Anything I wash will dry on the rack within a couple hours. I usually end up doing laundry at night and leaving it on the rack overnight.

Durability

The Wonder Wash is all plastic, except for the axle the machine spins on. I’d like to see a version with more durable metal components, but given the low price of the current design and the availability of replacement parts, this is barely worth mentioning.

Over the nine years I had the original Wonder Wash I cracked the base and snapped off the end of the handle. The machine was still functional with this damage. More recently, the lid began to leak when I spun the machine, which I assume was caused by the degradation of the rubber seal over time. This was enough for me to finally want to replace all three parts. The handle and base were readily available, but The Laundry Alternative released a new version of the Wonder Wash a few years ago, with the primary change being a snap attachment for the lid instead of a nob. I contacted them and they confirmed that they had no more stock of the old lid and that the new lid would not fit on the old bucket. So instead of purchasing replacement parts, I bought the new version of the machine. Given the price of the machine, I’m fine replacing it once every decade or so.

The new snap lid works just as good as the old knob lid worked when it was new. I don’t think there is a practical difference between the two. If for some reason you really want the old lid, the Avalon Bay EcoWash appears to be a direct knock-off of the original Wonder Wash.

The spin dryer is still going strong, in about the same condition it was in when I bought it nine years ago.