Into the Red Buttes Wilderness

Avagdu and I pulled into the trailhead around 7 PM. After getting our gear together, we decided to take advantage of the long summer evening to log a few miles. The trail into the Red Buttes Wilderness climbs steadily through pine woods. It’s dry and dusty with the lack of rain. But that’s to be expected. We’re back in California, after all.

Occasional glimpses of large slides and the valley below can be had through the trees. Soon enough, the sun sets behind the hills. I remove the headlamp from my pack and throw it around my neck. Avagdu stops a minute later to do the same. There’s another hour or so of good hiking to be got yet.

Our destination this night is Echo Lake. I don’t think it’s too much further down the trail. After I wet my feet in a stream crossing, I figure we must be close, but the sun is down, the moon not yet risen, and I’m worried I’ll miss the spur trail that goes off to the lake. Shortly after the crossing we’re surprised by a small wilderness camp: a shelter made of 4 upright posts and a few pine boughs for a roof, a table, a bit of firewood, and what is either an attempt at a chair or a Nessmuk-style fire. I can’t tell which. It’s an impressive setup. “Someone Ray Mears-ed it up,” Avagdu says. The only thing we can’t figure out is why the shelter is lashed together with duct tape rather than cordage. Or why the bundle of firewood is wrapped in duct tape.

It’s a bit after 10 PM now. We decide to take advantage of our luck and spend the night here. The shelter doesn’t look waterproof, but there’s no other flat ground around. It doesn’t feel like rain tonight anyway. There’s enough room for us both to throw our bivvies down underneath.

I had eaten before reaching the trail. The meal is still sitting in my belly. Forgoing dinner, I go off to hang my food. Avagdu decides to cook a small meal for himself – out of hunger, or just so that he’ll have a few less ounces to carry tomorrow. While we’re sitting around the fire pit, I spot a small mouse scurrying around the shelter. He seems disappointed that new tenants have moved in. Particularly because we had moved the old sock (his bed, I think) from the ground of the shelter to the table. After sniffing around for a while he scurries off.

We’re off early in the morning, with expectations of a short climb before arriving at the lake for breakfast.

Things don’t go as planned.

The grade steepens, as expected, but the trail keeps going on. Eventually we break out of the trees into a muddy meadow. Snow patches begin to appear. Somewhere in the meadow I loose the trail. By 10 AM we both feel that we should have reached Echo Lake. The mileage posted at the trailhead was only 4 miles, which we’ve certainly accomplished by now. I’m getting hungry, so I decide to stop in a patch of trees for a bowl of oatmeal. We both eat. After cleaning my pot I get out the map. It’s a large, ungainly thing. I plot our position and get a bearing to the lake. Not too far off, but I still don’t trust the mileage. It’s definitely further than 4 miles from the trailhead.

We climb up higher. The snow is constant now. We end up on a small knob above the lake. Echo Lake is surrounded by snow and looks to be still partially frozen over. Neither of us feel like venturing down for a visit. Our route now takes us up out of the basin onto the Siskiyou Crest. If we went down to the lake we’d just have to climb back up again. So we decide to forgo the lake and instead head higher, aiming for the saddle between Red Butte and Cook and Green Butte.

The slope we’re climbing is facing north. I hope that once we get over to the other side the snow will be gone. Or at least less. Before leaving for the trip I hadn’t been able to find any recent reports or conditions for the area. I figured we wouldn’t be getting very high and, hey, it’s California (the whole state is a desert, right?), so we didn’t plan for much snow.

I’m wearing my Merrell Trail Gloves, which aren’t exactly ideal for kicking steps. But going uphill isn’t too much trouble. We reach a bare scree field, climb it, and gain the saddle. I’m pleased to see that both the top of the ridge and the south slope are covered not by snow, but by Manzanita.

Just on the other side of the ridge is our goal: the Pacific Crest Trail. We’ll be on the PCT for the next few miles, which ought to help us make up for time lost in the snow. The PCT is the superhighway of the mountains – wide, tame, and well groomed compared to most wilderness trails.

Our route takes us west along the ridge, toward Red Butte. Only a few yards down the trail we come upon a group of three camped on the ridge. They had planned the same route as we, but also did not expect the trail to Echo Lake to be so long nor the snow to be so prevalent. It had upset their schedule. They no longer had time to complete the loop. Instead, they decided to spend some time enjoying the view from the ridgetop before descending and heading out.

The trail is wide and dry. It goes on for a bit before intersecting an old logging road. Just west of the junction both road and trail continue into a snow-filled basin. So much for dry feet! There’s a good stream of snow melt flowing here which we use to fill up our reservoirs, not sure where the next good source will be.

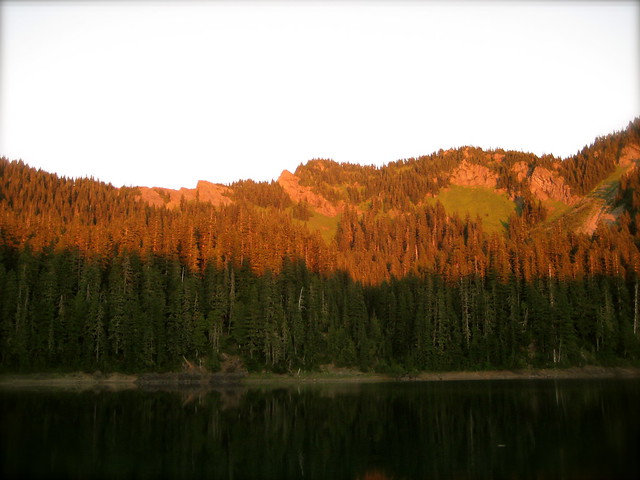

From there, the trail climbs over a ridge and down into another basin, which holds Lily Pad Lake. The road parallels the trail and ends in the same lake basin. I choose to follow the road, which is easier to spot under snow. The basin provides views of the other side of Red Butte, the namesake of this Wilderness.

Once across, both road and trail take a steep route up and out of the basin. I decide to take a route slightly longer but easier given the snow. Once gaining the other side, we’re once again in mostly dry territory with only occasional patches of snow. I find the PCT and follow that for a bit before loosing it in another snow field. On the other side, I find the road. Good enough.

The road ends at a fence made of stacked rocks. From there we can look down into this new basin and see the PCT. Lily Pad Lake sits below it. Both hold more snow. The ridge on the west side of the basin has more snow and looks steeper than any field we’ve yet encountered. We must climb that, but not yet. It’s early afternoon and my stomach calls for lunch.

It’s windy up on the ridge. There’s a small notch in the rock fence where I setup my stove, keeping it out of the wind. A pot full of noodles, a few mouthfuls of granola with dark chocolate chips, and I’m feeling copacetic in the sun. But we’re not getting any closer to the other side of the basin and Avagdu has finished his crackers and MRE peanut butter. It’s time to move on.

Climbing down from the end of the road we regain the the PCT. It is soon obscured by snow. The slope is indeed steep here – steep enough that I don’t feel safe crossing it without an ice axe or traction devices. But there’s a bare spot above. I make for that, where we can cross above the snow field and then come back down on the other side. I’m having flashbacks of last year in the Glacier Peak Wilderness.

We make it to the top, and across, but before heading back down to where we need to be there’s a finger of the snow field to descend. Avagdu goes first, sitting down on the snow and attempting a controlled descent that ends up being a glissade to the other side. I do the same.

It’s not much further till we reach a similar obstacle. But this time we can’t go up and around the snow. The only choice is to go straight across. I lead this one, slowly kicking steps across the field. It’s easier to cross on a diagonal line, heading slightly uphill. Eventually I end up above where I need to be, with Avagdu behind me. Below, the snow continues for 30 feet before reaching the trail, which at that point is bare. It’s a steep glissade without an ice axe to control the descent. The best option looks to be to sit and attempt to crab walk down, kicking in my heels to make steps as I descend. This works till about halfway, where a step fails and I slip, sliding down the rest of the way. It’s close – I almost miss the bare spot and end up in a tree well further down the mountain – but I’m able to slide enough to the right that I make it, with no problem other than cold hands from digging into the snow.

Meanwhile, Avagdu is above, watching the performance with some amount of trepidation. He sits down for his turn and I attempt to guide him in, instructing him to kick steps with his heels and aim for the log on the trail. The beginning is good. Then he slips and starts the glissade. He’s further to the left than I was, but he’s reaching for the handholds on the exposed trail and it looks like he’ll make it without trouble, until his reach turns into a somersault. Luckily the somersault takes him in the right direction and he crashes into a branch of the log or a bit of rock. I can’t see which. Later, he says that whatever hit him did so on his heavily padded hip-belt, which probably saved him some discomfort and bruising on the hip.

After a well deserved breather and a bit of water, we continue. It’s not too much longer before, predictably, the trail once again crosses into snow and enters a steep slope. This time it looks like we can go up and around along a tricky scree field, but a group of large boulders prevents me from seeing what is held in store for us on the other side.

We go for it, carefully making our way across the scree along the edge of the snow. It’s the most difficult part yet. On the other side, I climb up the group of boulders to getter a better view of the route above. It’s not a good sight. We’re almost at the top of the ridge, but directly across from us is another steep, snow covered slope. There’s no way around it, above or below, and I don’t want to attempt another crossing so steep without more tools. Directly above us is steep as well. We might be able to make it, climbing with both hands and feet, but there look to be a few cornices up there at the top. That makes me uncomfortable. Avagdu has come around by this time and points out a possible route, saying that there’s a few trees along there to break our fall. I start laughing. That’s exactly what I look for when I’m scouting out a route, but hearing it voiced out loud is somehow humorous. “Yeah, don’t worry, there’s some ground down there to break our fall!”

Another look around. It doesn’t look good. I still can’t see over the top of this ridge, so even if we make it up I’m not sure what waits for us further on. More of the same, likely, which will upset our schedule.

I suggest we turn around. Avagdu agrees. If we’re careful, we can take Avagdu’s suggested route a little further along, which will put is in intermittent trees. We can glissade from tree to tree, hopefully avoiding any big wells, and make it down to the bottom of the basin. From there, it’s a simple matter of crossing the basin (while avoiding a fall into the lake, which is still partially obscured by snow). The other side of the basin is clear of snow, so we can switchback our way up till we hit the trail or road, and then backtrack to the saddle between the two buttes where we first climbed up out of the basin and Echo Lake.

We reached the spot where we first joined the PCT. The camp belonging to the group of 3 is gone. They must have packed out ahead of us.

I scout out the ridge a bit, checking to see if there’s a better way down the north side than the route we took up. There doesn’t seem to be anything. Looking down from the spot where we finally gained the ridge on the way up, our path looks steeper than before. Funny how that works.

Avagdu and I both relax for a bit, enjoying the view and watching a few clouds roll in. The slope isn’t getting any less steep. After chucking a few rocks down to see where they land, we decide to go for it.

We descend the bare scree field and are back in the snow. Luckily, we can glissade down this time rather than having to climb up. It’s quick, and fun.

Just below where we now know Echo Lake to be we come upon the remains of an old fire ring. There are flat spots around that will make decent spots for us to pitch our tarps, but with the lake on one side and the muddy meadow on the other it looks like it will become too buggy for my tastes. We opt to continue down further, crossing the meadow and descending back into the woods.

At 7 PM we reach a spot with wide flat areas at the base of a cliff. There’s a small trickle of water in the back and the trees are sparse enough to let the sunlight in and allow some views of the sky. This will do for camp.

An abundance of dead wood lies on the floor. The novelty of actually picking dry firewood off the ground rather than having to break it out of trees encourages me to start collecting the makings of a fire. While Avagdu is pitching his tarp I take a spade-shaped rock to dig a small pit. Then I build a basic lay. Soon the flames are jumping.

The night brings heavy rain. The noise on the tarp is enough to wake me up a few times during the night. In the morning I wake but don’t rise for a couple hours, hoping that the rain will soon die down. When it turns to a light sprinkle, I venture out. Our camp has certainly become wet. Avagdu is up and about. He didn’t pack much in the way of insulating layers, so he’s chilly and wants a fire. All of the wood is now sodden. Even that up in the trees is wet, none of the branches being thick enough to protect those below them. It takes some doing, but eventually, with a bit of splitting, feathering, and a few other tricks, we rekindle the fire.

After breakfast the rain picks up again. Neither of us want to sit around outside getting wet, so we retreat to the tarps. The rain puts out our unattended fire.

We have no firm plans for this day. By late morning it appears that the rain won’t give up. We decide that rather than staying in the wet woods all day, it will be better for us to head out and continue on our road trip back up to Washington. A few hours on the road today will make us more likely to accomplish our goal of being in Portland for a meeting on the morrow.

As we break camp the rain continues. We descend lower into the valley. The rain becomes heavier. The sky seems like a torrent by the time we reach the bottom, and both of us are wet. The trailhead is reached shortly after, and there: shelter and some dry clothes.

I leave the mountains, sure in the knowledge that I will return. Perhaps to a different range, but to mountains none the less.

Give him a far reach of eye, the grasses rippling, the small streams talking, buttes swimming clear a hundred miles away. Give him… the clean, ungodly upthrust of the Tetons. They were some.